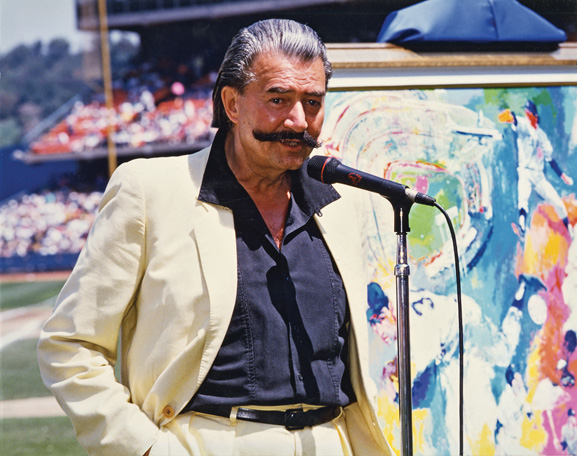

LeRoy Neiman accepts the Art to Life Award

Neiman has cited as especially influential in his development as an artist the work of Leonardo da Vinci and Rubens, “for spirit”; Tintoretto, “for space”; and Fragonard, “for feel.” Others include various Romantic realists, impressionists, post-impressionists, and fauvists; the French master of light and color Raoul Dufy; the Eastern European expressionists Kees van Dongen and Oskar Kokoschka; George Bellows and other members of the Ashcan School; and the abstract expressionists, especially Jackson Pollock and other practitioners of action painting, in which paint is applied directly by such means as splattering and dribbling.

“I sketch all the time,” Neiman said recently, speaking from his studio in the Hotel des Artistes, a landmark New York City building across the street from one of his favorite places, Central Park. In the same building he maintains an office, a penthouse pied-à-terre, and an apartment that he shares with his wife, the former Janet Byrne. To Neiman, a sketch is “a record—something to consult with” when planning a larger work. “I do about two dozen paintings a year,” he explains.

LEROY Neiman’s

Big Band

While a few of his works measure less than two feet by three feet, many are much bigger, including his most recent accomplishment, LeRoy Neiman’s Big Band, a 9’ by 13’ painting depicting eighteen hall of fame jazz musicians like Miles Davis, Louis Armstrong, and Billie Holiday. “Louis Armstrong was a friend and a nice, good man. He always said that jazz was a working man’s profession, as is art, which I agree with. I always felt a connection with the jazz guys,” Neiman says. The painting will have a West Coast unveiling on February 17, 2009 at Los Angeles’ Skirball Cultural Center.

“It’s one of the major pieces of my career,” Neiman says. “This is the largest easel painting I’ve ever done. It has every jazz musician I ever thought was really great. I’m kind of proud of it; I think it’s one of my best works.” As he does with all of his works, Neiman gave birth to Big Band after a long process of gestation. “I got started on it when I met Wynton Marsalis, who was always inviting me to come to his rehearsals over at Lincoln Center,” Neiman explains. Neiman would spend days watching Marsalis’ eighteen-piece band work their magic while he, in turn, worked his own, sketching the musicians creating their sounds. Before long, the sketches blossomed into a larger, singular work.

Neiman and Playboy

In the early 1950s, while freelancing at Carson, Pirie, Scott and Co., a Chicago department store, Neiman made the acquaintance of a young copywriter also in the store’s employ named Hugh Hefner. In December 1953, Hefner began publishing Playboy. A few months later, after a chance meeting, Neiman showed Hefner some of his paintings. Much impressed, Hefner brought Art Paul, Playboy’s art director, to Neiman’s apartment to see them. Paul immediately commissioned the artist to illustrate “Black Country,” a short story by Charles Beaumont about a jazz musician. His creation of those illustrations, which earned Playboy an award from the Chicago Art Directors Club in 1954, marked the inception of Neiman’s ongoing association with the magazine. “He’s one of my best friends to this day,” Neiman says of Hefner. “It’s a long, long relationship. I can’t say anything but the best about Hef and the magazine.”

In 1958, Neiman began producing sketches and paintings for a Playboy feature called “Man at His Leisure,” for which he also wrote the text. Appearing in the magazine for the next fifteen years, “Man at His Leisure” showed the artist’s impressions of sporting events and social activities, many of them at some of the world’s most socially prestigious locales. Between 1960 and 1970, Neiman produced more than one hundred paintings and two murals for eighteen Playboy clubs. “I traveled all over the world for Playboy for fifteen years. Playboy made me visible and introduced me to all the important events and people that were going on at the time. It put me in the middle of the action and helped give me a fabulous life. I’ve enjoyed every minute of it, and I think the joy that I’ve experienced is reflective in the work,” Neiman reveals. “I’m slowing down now, but when I look back at the adventures I’ve had socially—and every other way—I owe a lot of it to my association with Playboy.”

Neiman sums up his philosophy of work and life very simply: “I paint from life. When I paint a canvas, it starts out with nothing, and it winds up a Neiman.”

An evening with LeRoy Neiman & All That Jazz is presented by the California Jazz Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization formed to provide assistance to musicians and others in need who have made substantial contributions to jazz