Best Gossips on Renaissance Artists by Giorgio Vasari

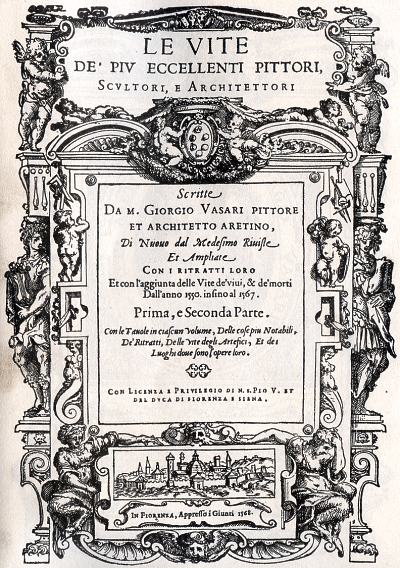

Known as the first art historian, Giorgio Vasari wrote the legendary book The Lives of the Artists. The book was published in 1550 and followed contemporary artists’ lives and works (mostly) from a first-hand account. As a major secondary source in the history of Italian Renaissance art, Vasari mentions only those he believes were the greatest artists of his time. For instance, Michelangelo, Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, Titian, Ghiberti, Filippo Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Sandro Botticelli (just to name a few). And what else would Vasari deem to be of the utmost importance to mention in his book of famous artists? Only the best and most scandalous gossip of the 16th century.

Title page of the 1568 edition of Giorgio Vasari’s book, Le Vite. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Giorgio Vasari

Giorgio Vasari was an Italian painter, architect, engineer, writer, and historian. He is best known for writing The Lives of the Artists and as the first art historian in history. (Pretty much the one who invented the discipline of art history.) Born in 1511, Vasari grew up in the small town of Arezzo in central Italy. At 16, Vasari moved to Florence to take up artistic training while being cared for by the Medici family. Eventually, he became friends with Michelangelo, whose work influenced his own. Then, in 1532 when the Medici family was reinstated their power, Vasari lived at their court in Florence. He traveled around Italy for the next decade, becoming friends with artists.

While in Rome in 1543, he had dinner with Paolo Giovio, a scholar and art historian at the papal court. During the dinner, it was suggested to him that he should write biographies of all the great Italian Renaissance artists. By 1547, he had finished writing The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (also known as The Lives).

It was praised by Vasari’s contemporaries and quickly became the single most important secondary source in the history of Italian Renaissance art, containing not only a wealth of facts and attributions but entertaining anecdotes about the private lives of the greatest artists of the Italian Renaissance.

Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella

A new translation of Giorgio Vasari–The Lives of the Artists, 1998.

According to Giorgio Vasari, Sandro Botticelli grew up with an unusually whimsical mind that perturbed his father. Out of desperation to make his son normal (to his expectations), he placed him with a goldsmith to learn the trade. His father might not have realized during the 15th century that goldsmiths and painters were in constant contact. As a clever boy, Botticelli developed a likeness for painting and eventually became known to the Medicis. After completing numerous paintings for Lorenzo ‘Il Magnifico, Botticelli was requested by other Florence homes. At these homes, Botticelli began making a name for himself through numerous female nude paintings (for which he is most famous today).

While Vasari was writing the book, he says the Birth of Venus was still at Castello, Duke Cosimo’s villa in Florence. As an incredible secondary source, Vasari also describes the painting, saying, “…and those breezes and winds which blew her and her Cupids to land.” He also says that Botticelli expressed himself with grace through the painting.

Although Giorgio Vasari praised most of Botticelli’s works, he did criticize him by spreading gossip about how he spent his earnings. Vasari says that even though Botticelli earned a lot of money, he wasted it all through carelessness. Throughout the chapter on Botticelli, it is unclear how much Vasari respected the painter. He often told stories about jokes Botticelli pulled on other artists but would then discuss his incredible skill as a painter. Although the way he speaks of Botticelli’s death raises suspicion, since he describes him as weak and useless…

2. Michelangelo vs. Raphael

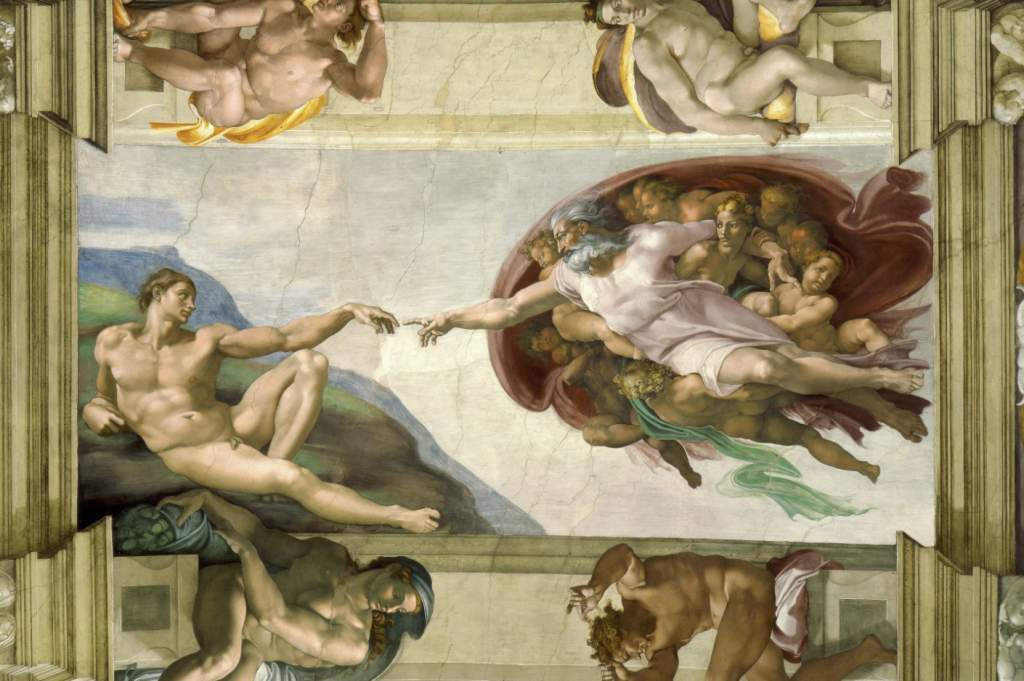

Michelangelo, Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel ceiling, 1511-1512, Sistine Chapel, Vatican. Artsy.

Although being mentioned in Lives was a great honor for a Renaissance artist, Giorgio Vasari’s favor over Michelangelo was unequivocal. Probably the best gossip spilled by Vasari was the quarrel between Michelangelo, Raphael, and Pope Julius.

According to Vasari, Pope Julius commissioned Michelangelo to make his tomb for St. Peter’s Basilica. The Pope asked Michelangelo for this piece since he was the greatest sculptor of his time. Michelangelo began sculpting the tomb but was called away for another project in Bologna. During his time away, Raphael and Donato Bramante (architect and relative of Raphael) convinced the Pope that it was bad luck to build a tomb while one was still alive. And that upon Michelangelo’s return to Rome, he should paint the vault of the Sistine Chapel in memory of his uncle Pope Sixtus IV (who commissioned the construction of the chapel in 1473).

Revenge

At first, this sounds like Raphael and Bramante were trying to do Michelangelo a favor. It was the exact opposite. In an act to throw Michelangelo off his perfectionism in sculpture, Raphael hoped that the fresco ceiling would be a complete disaster. Michelangelo had absolutely no experience in frescos, and when he returned to Rome, he suggested Raphael complete the Sistine Chapel, not himself. After realizing the Pope insisted on his work for the ceiling, he agreed and began working on the most difficult commission of his career.

Of course, Michelangelo did not fail, and the Sistine Chapel ceiling is a masterpiece of Renaissance art to this day. Vasari also did not let Raphael get away with this deception. So as punchy revenge, Vasari claims that Raphael died from having too much sex and that he lived more like a prince than a painter.

3. Feud at the Florence Cathedral

Lorenzo Ghiberti, Baptistery of S. Giovanni, Gates of Paradise, 1425-1452, Baptistery, Florence, Italy. Artsy.

In 1401, Filippo Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Lorenzo Ghiberti were commissioned to compete with a design for the doors to the Baptistery of San Giovanni. Although other artists entered the competition, Donatello and Brunelleschi agreed that Ghiberti’s design was the best. Although according to Vasari, Brunelleschi’s politeness did not last long.

Brunelleschi is known for his architectural design of the dome atop the Duomo in Florence. While it was an engineering puzzle to design this dome, Brunelleschi asked for other architects to help with the design. Vasari claims, though, that Brunelleschi wanted to show off his “exceptional talent” rather than actually needing help from professionals.

Filippo Brunelleschi, Cathedral Santa Maria de Fiore, 1436, Duomo of Florence, Florence, Italy. Museum website.

Unfortunate Fate

Finally, in 1420, Brunelleschi created a proposal for the dome’s design and won the commission. Although, to his surprise, the officials believed no single architect could complete this on their own. Therefore, they paired Brunelleschi and Ghiberti and, as a slap in the face, gave them the same salary.

Vasari claims that Brunelleschi immediately began scheming for ways to fire Ghiberti. Since Brunelleschi believed he should receive all the fame for his engineering and architectural skills. When Brunelleschi became ill, workers asked Ghiberti for decisions about how to proceed, and apparently, he said he would not make major decisions without his partner. As a result, the officials questioned Ghiberti’s capability. This humiliation brought great pleasure to Brunelleschi, who is remembered as the founding father of Renaissance architecture and the first modern engineer.

Vasari’s Legacy

While art historians don’t know what gossip is true or what Vasari elaborated on, The Lives of the Artists is the best source of the Italian Renaissance. Without it, the discipline of art history might not have existed. For all us art historians, we are very grateful for the ridiculous gossip spread by Giorgio Vasari.

Bibliography

1.

Bondanella, Julia Conaway, and Peter Bondanella. Giorgio Vasari–The Lives of the Artists, 1998.

2.

Stapleford, Richard. “Vasari and Botticelli.” Mitteilungen Des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 39, no. 2/3 (1995): 397–408. Accessed 22 Aug 2022.