Elizabeth A. Sackler

In searing, provocative images, nearly fifty works on display at the Center for Feminist Art from feminist artists like Kiki Smith and Lorna Simpson explore gender inequality and perceptions. They participate in more than artistic exhibition; they celebrate the groundbreaking recognition of a movement both artistic and political.

The exhibit mirrors the passionate commitment to social change and gender equality of founder and financier Elizabeth Sackler. The center is her brainchild; it’s the first museum collection devoted not just to female artists but to feminist art.

For Sackler, it’s an extension of lifelong passions: art and social activism. Coming of age in an era of social unrest and social change, Sackler was strongly influenced by the women’s movement of the 1960s. “I believe in equality and justice for all people. I grew up in a family where there was social parity. Sexism was not part of my world,” she says today. What was part of her world was a love of art and a desire to enrich others. Her father, a prominent physician, was known not only for his contributions to medicine but also for his art collections and philanthropic endeavors. Fascinated with Asian art, he bequeathed his art collections to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and to Princeton and Harvard.

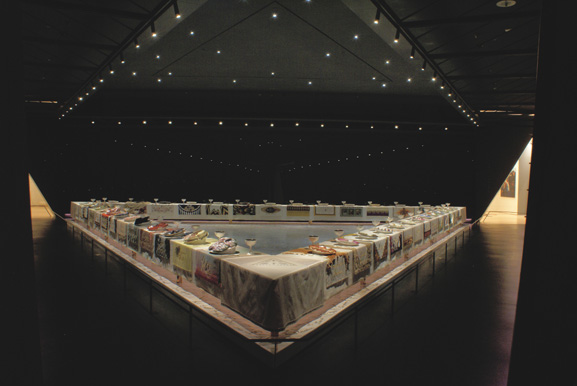

“The Brooklyn Museum was extremely excited,” remembers Sackler. “The transfer of The Dinner Party took a nanosecond. It’s a launching pad …it has contextualized the erasure of women in history.”

The Dinner Party is still center stage here; it’s part of the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art, established in 2007. The center also houses resources for scholars and historians. The Feminist Art Base is the first digital archive devoted solely to feminist art with images, video and audio clips, biographies and feminist artist statements. “It’s been very successful,” says Sackler. “Its appeal crosses generations.”

While feminism is part of the mission, feminist art as a movement is hard to define. “To me, it’s political art about the suppression of women,” reveals Sackler. The feminist art movement also pioneered the use of performance and audiovisual media while reintroducing art as a tool for social change. Sackler is devoted to the continued success of her project. The mission is to educate and raise awareness. “I invite people to speak,” she says. Recently, Gloria Steinem spoke about sexual trafficking.

While the women’s movement has changed history, there’s still work to do. “There’s still a need for parity for women, a need to fight misogyny,” asserts Sackler. “There’s still a glass ceiling. Women are paid less than men. They’ve also been very significantly erased from the art world.”

But at the Brooklyn Museum, women are equal. “My parity has to do with wall space!” she enthuses.

The commitment to equality and justice has led Sackler to other causes. An accomplished public historian with a doctorate, Sackler has fought for the rights of Native Americans in the art world.

Recently, Sotheby’s put three masks up for sale that belonged to the Hopi and Navajo tribes. When the tribes wanted them back, Sotheby’s refused to return them. Sackler bought the masks herself and returned them to the tribes.

As the head of two foundations, Elizabeth Sackler is a philanthropist committed to social activism. “My baby is the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art. I’m very proud of it,” says the devoted philanthropist. The challenge is to rewrite history, restore women artists to cultural memory, and change the future.