Käthe Kollwitz: Germany’s Greatest Female Artist

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) was one of Germany’s greatest artists and she holds the distinction of being the only woman artist to make it into Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art. In 1920, she became the first female member of the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, and there are today three museums in Germany dedicated to her life and work, in Berlin, Cologne and Moritzburg.

Her artworks, although masterful, are rarely cheerful, but this is unsurprising given the dark and turbulent times through which she lived. She was born Käthe Schmidt in 1867 in the then Prussian city Königsberg, which is now the Russian exclave Kaliningrad. In 1871 the German Empire came into being, only to collapse in 1918 after the First World War. The short-lived Weimar Republic gave way in 1933 to the so-called Third Reich, which itself dissolved a few weeks after Käthe Kollwitz’s death on the 22nd of April 1945.

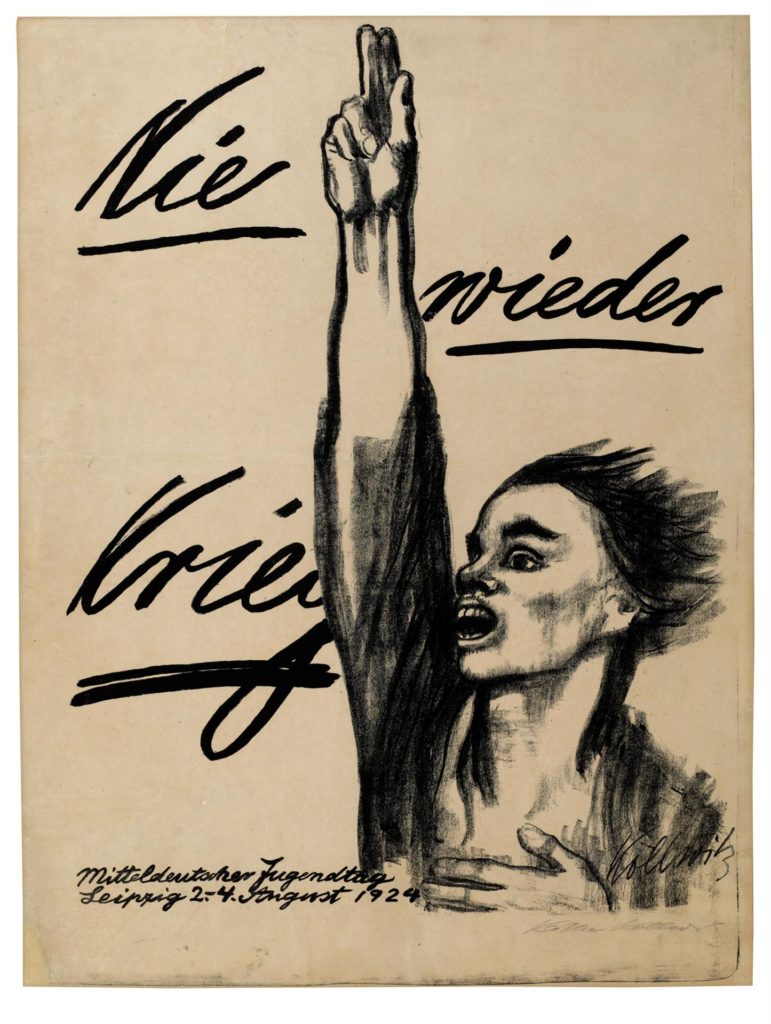

She married Karl Kollwitz in 1891 and they had two sons, Hans and Peter. Abandoning painting in favor of printmaking (which is mass-producible and therefore able to reach more people), Kollwitz rose to prominence at the end of the 19th century with her series of prints depicting the Silesian Weavers’ Uprising of 1844, which was followed in the early 20th century with a series on the German Peasants’ War. War, specifically its futility, was, therefore, a common theme in her works, and Kollwitz was a committed pacifist, as evidenced by the following poster in which a woman declares Nie Wieder Krieg (Never War Again).

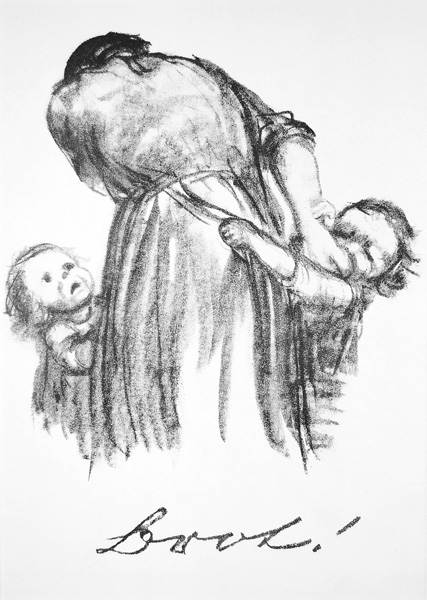

The Kollwitz family lived in the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg in the northeast of Berlin. Many of Kollwitz’s harrowing works depict in blunt detail the suffering of Berlin’s poor, such as the following, which shows two starving children begging their desperate mother for Brot (bread).

When the First World War broke out, Kollwitz’s youngest son, Peter, begged his parents to allow him to enlist, despite being underage; he died in October 1914 and Kollwitz’s subsequent grief and guilt never left her. It took her almost two decades to give artistic expression to the sorrow that she felt at the loss of her son: The Grieving Parents, depicting Kollwitz and her husband, watch over Peter’s grave in the Vladslo German war cemetery in Belgium.

Kollwitz was one of the signatories of the “Urgent Call to Unity” in 1932, which was a last-ditch attempt by leading German artists, authors and scientists – among them Albert Einstein – to prevent the rise to power of the National Socialists. When the Nazis seized power in 1933, Kollwitz was forced out of her position at the Academy of Arts and threatened with arrest, leading to a slowdown in her artistic output.

In 1940 her husband died from illness and in 1942 Kollwitz lost a grandson, also called Peter, in the Second World War. Forced to evacuate Berlin in 1943, she lived out her remaining years in Moritzburg. After the war, Kollwitz and her work came to be seen as a symbol for the suffering of all Germans during the two terrible World Wars.

Today there is a Käthe Kollwitz Prize which recognizes the achievements of modern artists living and working in Germany. In Berlin, Kollwitzplatz is a popular hangout in now-trendy Prenzlauer Berg and a statue of Kollwitz (by German sculptor Gustav Seitz) can be seen there.

Visitors to Berlin should certainly visit the Käthe Kollwitz Museum, which contains over 200 of her drawings, posters, prints, sculptures, and woodcuts. If you’re in Berlin, make sure also to pay your respects at the Neue Wache (New Guardhouse) on Unter den Linden, just a few minutes from the Brandenburg Gate.

This Prussian Guardhouse (inaugurated in 1818) was turned first into a memorial to the victims of the First World War, then to the victims of the Second World War, and finally, in 1993 it was rededicated to all the victims of war and dictatorship. Inside is an enlarged version of Kollwitz’s sculpture Mother with her Dead Son, which represents the grief of Kollwitz at her son’s death as well as the anguish of all parents at the suffering caused by war. It resembles Michelangelo’s Pietà, but with far more pathos because Kollwitz knew there was no chance of a resurrection. An oculus above the artwork lets in the rain and snow. As a testament to the futility of war, Kollwitz’s Mother with her Dead Son is unparalleled.

For more information on Käthe Kollwitz, see Neil MacGregor’s Germany: Memories of a Nation.