Andy Warhol: Religious Artist for a Secular Society

When I first saw a photo of Andy Warhol he was in a wig and wearing lipstick, I thought what an interesting woman. And he was of course one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. He blurred the boundaries of high and low culture. He changed how we look at art. Read the story of Andy Warhol!

Andy Warhol and Pop Culture

Andy Warhol (1928–1987), an American artist, grew up in Pittsburgh during the Depression. He was a child of working-class immigrants from Austria-Hungary. Obsessed with celebrities at an early age, he would devour movie magazines. He would then write fan letters to his favorite stars.

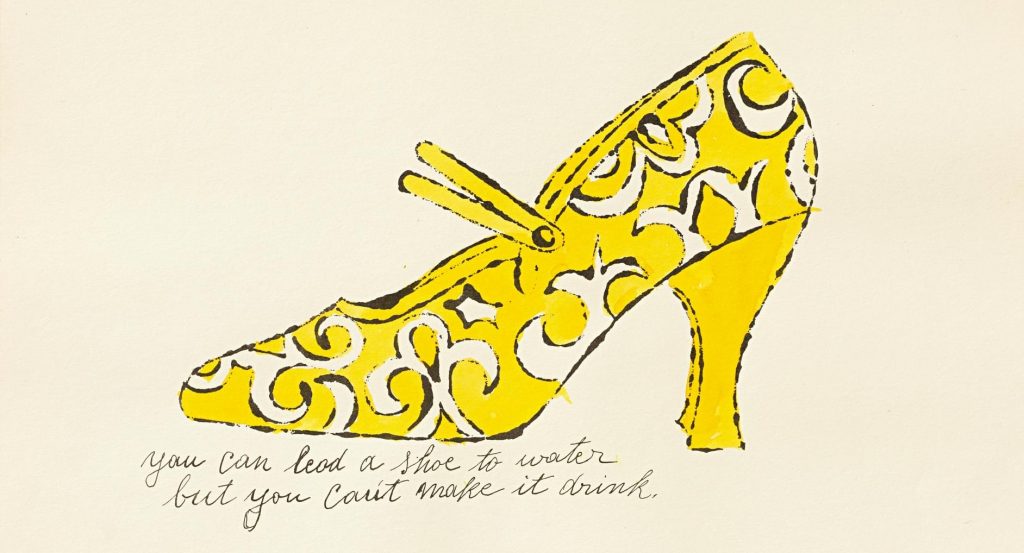

In the 1950s, Andy Warhol worked as a designer for a shoe manufacturer. He was an early adopter of the silkscreen printmaking process. At that time, Warhol developed his “blotted line” technique. He applied ink to paper and then blotted the ink while still wet, commenting that:

When you do something exactly wrong, you always turn up something.

Andy Warhol, Popism: The Warhol Sixties, 1980.

The 1960s were a time of consumer boom, mass media, and mass production. Advertisers pushed their products to the market. Consequently, people were bombarded with images, and art often reflected that. Artists like Andy Warhol used recognizable images to reach mass audiences. He combined hand-painted backgrounds with photographic silk screen printed images to create unique works of art. In the process, he changed how we look at art, transforming the concept of uniqueness and originality.

Andy Warhol and His Diptych

As one example, Andy Warhol depicted the actress Marilyn Monroe in 1962, shortly after her death. His Marilyn Diptych is a silkscreen painting with 50 images of the actress. He deliberately chose a basis image from a publicity photo of the 1953 film Niagara. This was the peak of the actress’s fame. Warhol vividly colored half of the diptych while he made the other half in black and white.

By repeating the image, Warhol evokes Marilyn’s celebrity status. Frozen in time, with heavy-lidded eyes and parted lips, she becomes the personification of glamour. This way, he effectively immortalizes Marilyn as the sex symbol of the 20th century. The effect of fading reveals the transience of life and the imminence of death. But it also speaks of a celebrity’s fame, which can often erode over time.

Furthermore, Andy Warhol hints at the superficial nature of celebrity and beauty. In this work, he is questioning the idea of perfection. The Marilyn Diptych does not represent an idealized beauty. Her face does not quite match the gaudy color behind it. Moreover, looking at her face, we cannot say what kind of person she was.

Andy Warhol’s Inspiration

On the face, Andy Warhol had a retinue of bohemian eccentrics. However, he spent most of his life living with his mother, Julia. Perhaps she was the greatest influence, especially in his early life. When Andy was a child, she decorated their home with her own folk art. She inspired him to develop his artistic side.

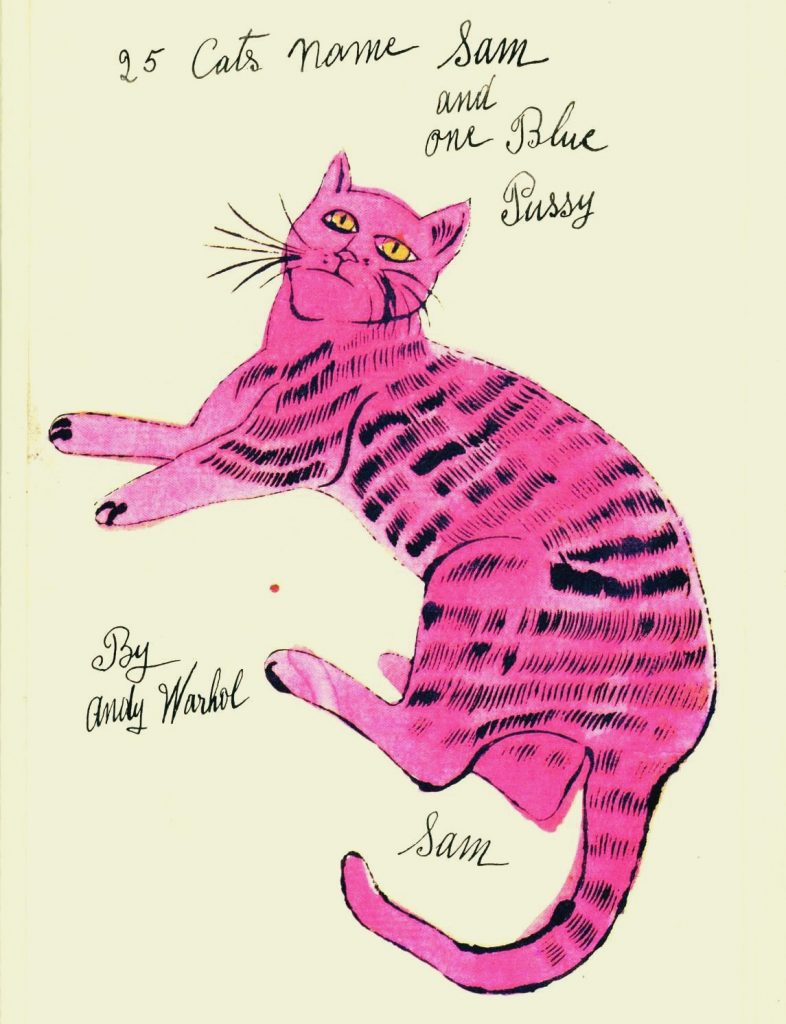

Warhol admired her artworks and often asked her to contribute her calligraphy to his projects. For example, her distinctive script accompanied his book 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy. At one point, she moved with him to New York. Together they rented an apartment, where they kept 25 cats, including Sam. She cleaned the apartment, cooked for him, and prayed with him every morning.

The Question of Faith

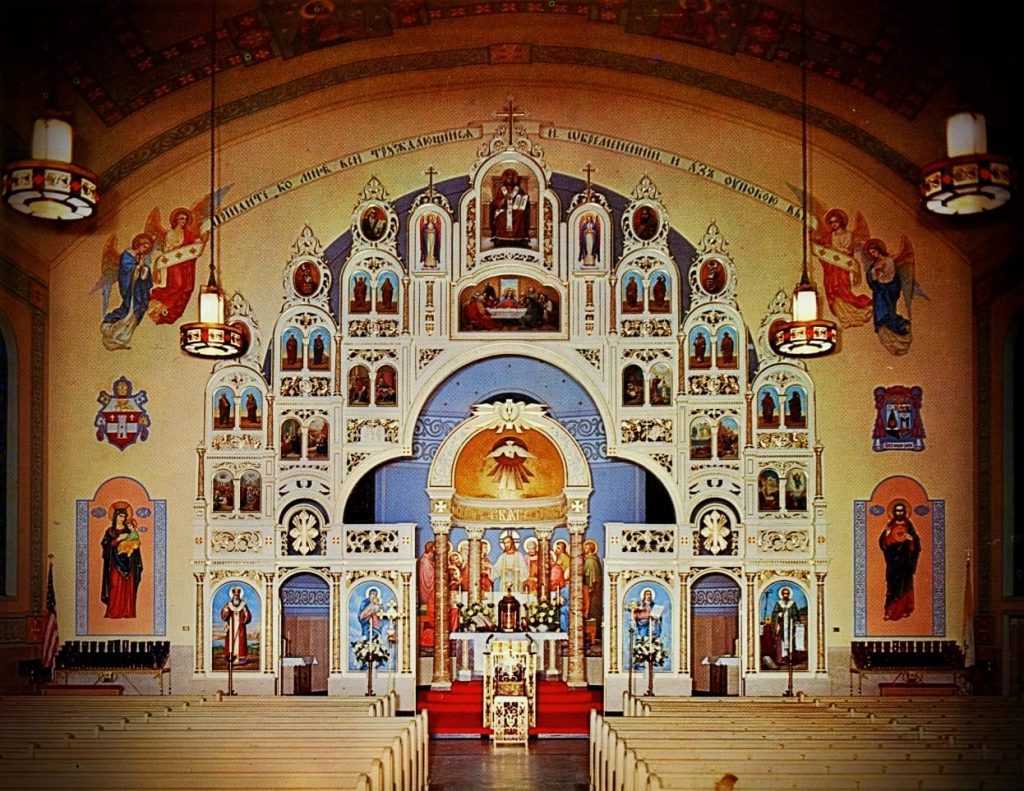

In fact, Andy Warhol was a closeted Byzantine catholic. He kept an altar with a crucifix and a prayer book on his bedside table. His mother knew the liturgy by heart. Furthermore, he went to John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church to pray most days. There, he would spend hours in front of the iconostasis, a wall that separates the nave from the sanctuary.

Apart from the dreams of celebrities, the church was the young Andy Warhol’s other escape from poverty. It would lead to Warhol’s two passions religion and celebrity being fused together. He would contemplate the figures of saints stacked repeatedly across the screen. It was here that his visual language was formed.

Andy Warhol and His Icons

The highly stylized Byzantine icons made a big impact on Andy Warhol. They are flat and lack the modern understanding of depth. Icons were often made using stencils, reminiscent of Warhol’s screen-printing process. Mass-produced icons were also created by a team of anonymous artists. It is something that Andy Warhol would later imitate with his assembly-line method of production.

Andy Warhol idolized women. In his works, Jackie Kennedy, Grace Kelly, and others appear as superhuman beauties or even martyrs. Moreover, he transformed them into deities. The Marilyn Diptych references a form of Christian painting. A diptych is usually a small portable piece on two hinged wooden panels used to spread Christianity to the masses. He would depict his first Marilyn as an icon and an object of worship like the Catholic image of the Virgin Mary. Here is Marilyn, as a religious icon herself.

The Last Supper

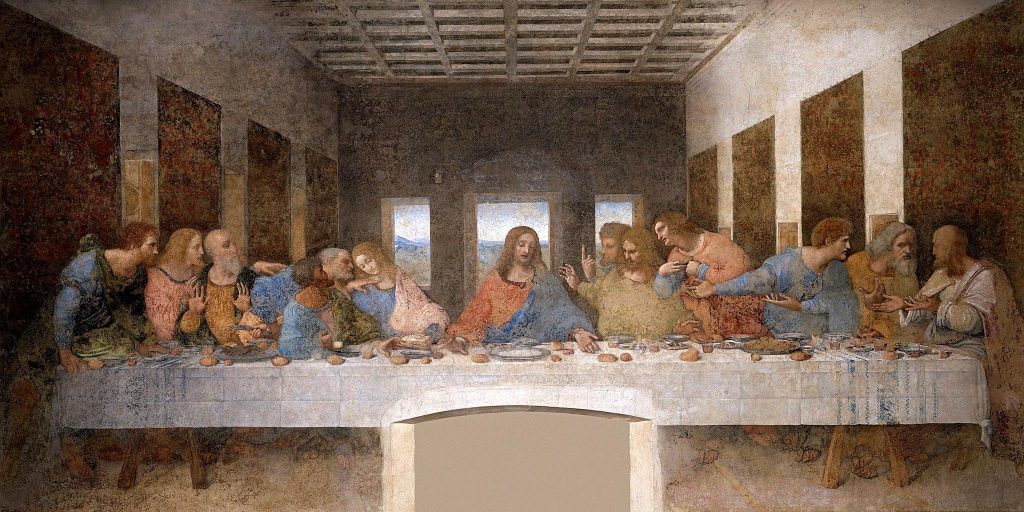

In the final decade of his life, Andy Warhol received a commission to work on a Last Supper series. He used a commercial reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper famous mural painting to create more than 60 silkscreens. Leonardo’s image had a prominent presence in Warhol’s life. His mother’s Bible featured a reproduction of the image. Another copy probably hung in the family’s kitchen.

Andy Warhol repeats the famous supper scene 60 times. In his black and white artwork, he makes the piece look like a post-modern building, encased in concrete. This image reminds us that Warhol’s works were not originals in the traditional sense. The blurred line between originality and reproduction often comes up in his art. What is more, the grid organizes and repeats the image. Consequently, the whole work resembles a series of film strips placed side-by-side.

Religious iconography would become more important in Warhol’s later art as he began to confront his mortality. The images of the eve of Christ’s crucifixion marked the end of Warhol’s own career and life. Returning to New York from the opening of the exhibition in Milan, he was admitted to the hospital for gallbladder surgery and died.

Although often copied and referenced, Leonardo’s Last Supper is still one of a kind. By contrast, when confronted with Warhol’s repeated Sixty Last Suppers, we become de-sensitized to it. He blurs the distinctions between the sacred and the profane, high art and commercial design. This process reflects Warhol’s transformation of a deeply religious work into an image whose profound message has become muted through repetition.

Sacred and Profane

With a background in advertising, Andy Warhol understood the power of images like no one else. He used religious symbolism and applied it to America’s newest faith. Andy Warhol had an extraordinary ability to find the sacred in the profane, and the profane in the sacred. Like so many successful Americans he was a product of the immigrant experience who himself became an icon.